This article is about an itinerary to discover the gates of the Theodosian Walls. Below, you can find out the route:

How to Get

From Sultanahmet to Yedikule (our first stop), you can get there via:

| By Car 🚗 | Follow the route of Kennedy Street, and then you can park your car at İSPARK Parking Lot at Samatya. You will need to walk to the first stop for about 10 minutes, There is a road (10. Yıl St.); however, it can be pretty challenging to find a parking lot during the itinerary, so we do not recommend driving a car along the route. |

|---|---|

| By Tram & Suburban Train 🚊 | You can take the T1 Tram to go to Sirkeci, and you can either take the T5 Tram to go to Yedikule or take the Marmaray line (Ataköy/Halkalı direction) to get off at Kazlıçeşme station. |

| By Bus 🚌 | There is no direct bus to Yedikule from Sultanahmet, but you can continue your journey with bus. If you take any bus from 10. Yıl Street (click the location of the bus stop), you can get off at the corresponding stops along the route. The bus stop names are the same as the gates they serve. |

| By Bike 🚲 | Surprisingly, despite Istanbul’s hilly terrain and frequent traffic jams, it’s possible to enjoy a pleasant cycling experience. A little-known bike lane follows the T5 Tram route from Sirkeci to Kazlıçeşme, our first stop. Also, the pavements along this itinerary are wide enough to make cycling generally safe. |

About The Walls

The Walls of Istanbul have many stories, and they are one of the oldest surviving city walls in the world. Primarily constructed in the Theodosian era, which gave his name to the walls.

The topographic map of Constantinople (R. Janin, Constantinople Byzantine. Developpement urbain et repertoire topographique Road network and some other details based on Dumbarton Oaks Papers 54)

The Byzantines had an advanced defense system, mainly due to the strategic location of trade routes in the Middle Ages, which connected China to Europe. They were successful in deterring tens of nations, except for the Ottomans.

Let’s explore these famous walls, part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site, in two different parts:

The Land Walls

These walls were the strongest, with three different layers. First, enemies had to pass through a moat, and then they had to climb three walls: the low, outer, and inner.

The outer wall was approximately 2 meters thick at its base and rose to a height of 9 meters. It featured arched rooms inside and a walkway with battlements on top, allowing guards to patrol or defend the city. People could reach this wall either through the main gates or through small hidden doors (called posterns) located at the bottom of the inner towers.

The moats from the Byzantine era have been used as a truck garden for centuries.

The Sea Walls

There is only one wall line covering the entire seashore because the narrow paths between residential areas were enough to besiege the enemy in the event of an attack.

The center of trade was the edge of the Golden Horn, now known as the Eminönü district, where the Spice Bazaar was located. In case of war, the narrow strait from Eminönü to Galata was closed with a chain to block the naval access of the enemy.

Considering the notorious fame of the Greek fire, the enemies had little chance of getting burned, even though in the sea, thanks to its ability to burn inside water.

The First Stop: Yedikule Fortress

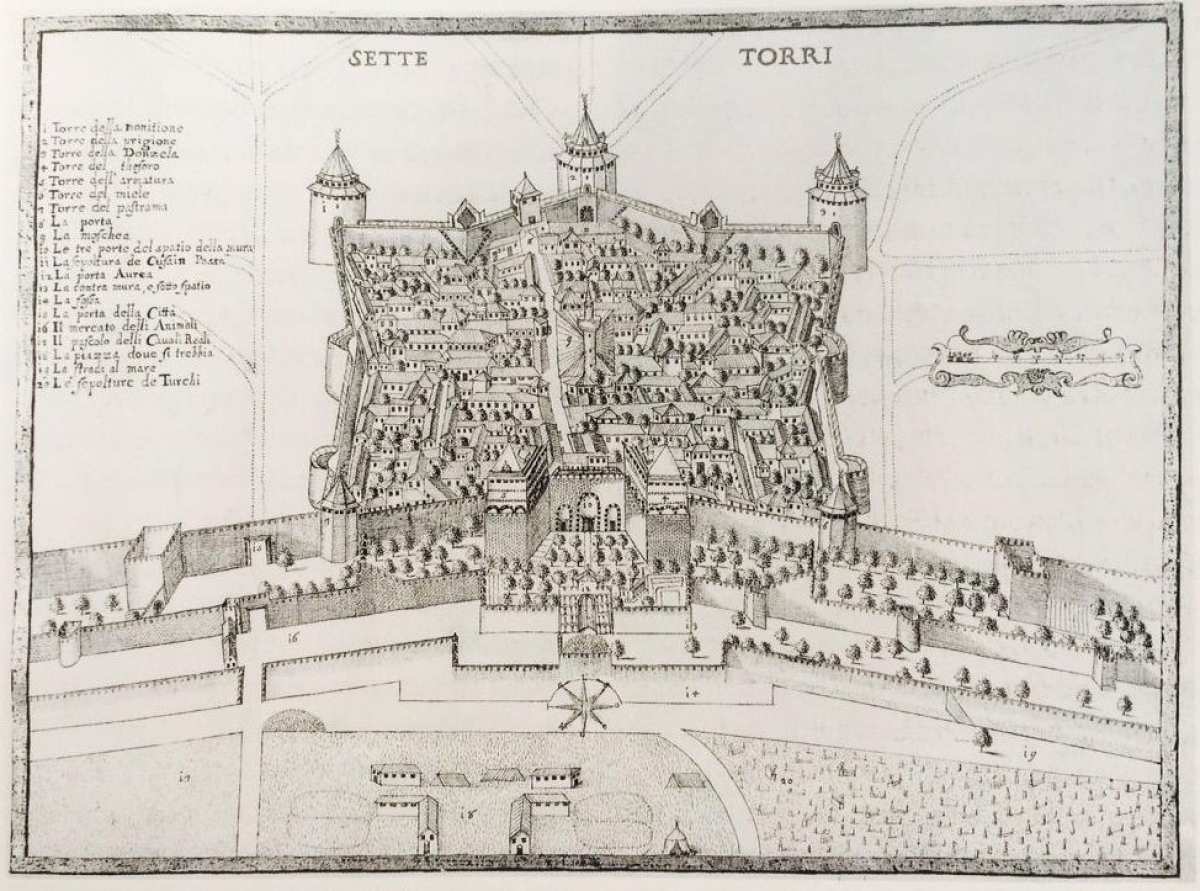

We start from our tour from the south. This section of the land walls was not only a fortress but also featured seven towers, serving multiple purposes, providing defense, celebrating the Byzantine conquest, and housing dungeons for political prisoners, including the Sultan himself.

The Golden Gate and the Castle of Seven Towers in 1685. (Mango, Cyril (2000), "The Triumphal Way of Constantinople and the Golden Gate, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 54)

Inside the complex ran a street called Via Egnatia, which once led all the way to Rome, the capital of the empire. After Constantinople became the new capital, Theodosius II built additional walls with a grand ceremonial gate known as the Porta Aurea, or the Golden Gate. This gate was primarily used for triumphal processions and took its name from the gilded decorations that adorned it.

The Golden Gate (Porta Aurea), Yedikule Fortress Museum

The Ottomans added three additional towers to the existing Roman ones, which gave the fortress its name “Seven Towers”, or Yedikule in Turkish. It later served as a garrison and housed the Imperial Treasury. In the 17th century, it was transformed into a notorious dungeon, marking a tragic end for Osman II, who was imprisoned there after attempting to curb the power of the Janissaries.

In the wake of the Industrial Revolution, the walls lost their defensive function, and new houses were built within the courtyard. Today, the only remaining example of the civil structures is the mosque at its center. The museum also features a café and hosts open-air events throughout the year.

The prayer room dates back to the 15th century, following the conquest of Constantinople.

Don't forget to pick up some flowers while walking on our second route, which offers a lovely view of the walls!

The florist at 10. Yıl Street, Yedikule Fortress in the background

Belgradkapı

Our second stop is Belgradkapı, the Belgrade Gate. It was one of the public gates of both the Roman and Ottoman empires, and it remains in use in modern-day Istanbul. Inside the fortress, staircases lead up to the towers, while walkways, passageways, and gates connect the ground floors to the city’s outer walls. This gate has an interesting story compared to the others.

Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent settled the Serbs in this neighborhood to benefit from their craftsmanship. The same reasoning applies to the Belgrad Forest, where the Serbs were responsible for maintaining the aqueducts and the roads leading to the freshwater springs. Inside the walls stands a Serbian Orthodox Church called Panagia Belgradlu, which translates to “Virgin Mary of Belgrade.”

Renovated parts of Belgradkapı feature cozy libraries that offer complimentary water, tea, and internet.

Fortunately, thanks to recent renovations by the municipality, it became an open-air museum with free admission. Passing through the gate, on both the left and right sides, the museum features two small but cozy libraries that offer complimentary tea, water, and internet.

Silivrikapı

The Silivrikapı (Silivri Gate) lies to the north of the Belgrade Gate and is distinguished by its two polygonal towers, both of which are still standing today. The Greeks referred to it as “Pege”, named after the nearby Church of Zoodochos Pege, meaning “the Life-Giving Spring.” The name Pege remains visible on the southern wing of the staircase.

During the Late Byzantine period, the name evolved into Selivria (modern-day Silivri), after a Byzantine city to which the road from this gate once led.

Silivrikapı (Silivri Gate)

On the upper section of the gate, one can still see the names "Basil" and "Constantine" inscribed. The outer wall with the arch was added during the Ottoman era, though the original Byzantine masonry remains clearly recognizable beneath it.

Following the Ottoman conquest of the city, Sultan Mehmed II established a new neighborhood within the city walls. The gate was later restored after the Great Earthquake of the 16th century under the reign of Bayezid II.

To the right of the entrance stands the tomb of Elekli Dede (meaning “Grandpa Sieve”). The famous 17th-century traveler Evliya Çelebi recounts that Elekli Dede was said to have eaten only food sifted through a sieve made from animal hide.

Today, the gate has been renovated following the 1999 earthquake and serves as a passage connecting the city’s inner and outer parts.

Mevlevihane Kapısı

Mevlevihane Gate (The Gate of the Mevlevi Lodges) has borne many names throughout history, each with its own story. The Byzantines called it the Rhesion Gate, and its name is mentioned on restoration inscriptions in Lento. Other Byzantine names include Polyandrion or Myriandrion (“Many Men” / “Thousand Men”), probably referring to the graveyards surrounding the gate.

The Russians later referred to it as the “Russian Gate” due to their historical presence in the neighborhood. During the Byzantine period, the Russians, who had not yet converted to Christianity, settled around the city and rebelled to gain free access to it. In the end, they won this struggle and subsequently gave the gate the name of their own nation.

Looking at the front gate, you can see a blank section of the inscription where a Byzantine heraldic emblem once stood, an eagle with two heads.

Also, the Byzantines were fond of watching chariot races at the Hippodrome of Constantinople. There were four competing teams, each represented by a color: red, green, blue, and white. The staunch supporters of the red team lived around this area of the city walls, which is why the gate became known as “The Gate of the Reds.” As time passed, only two teams remained, the Greens and the Blues.

The gate’s exclusive spirit found a curious echo centuries later in the Mevlevi dervishes. As part of their tradition, the whirling dervishes preferred to live away from the public eye, choosing seclusion over spectacle. They avoided areas where orthodox Islamic practices were dominant, which is why their lodges were often nestled near cemeteries, symbolically the opposite of this gate’s lively, worldly energy.

A whirling dervish (Semazen in Turkish) with a white dress and a tall conical hat

Today, after meticulous restoration work by the local municipality, the gates welcome visitors once again. Within this newly renovated complex, a small photography exhibition awaits, with libraries offering free internet, tea, and water, located inside the tower on the left side of the second inner gate.

Fetihkapı

Fetihkapı (The Gate of Saint Romanus) holds remarkable historical significance. Geographically, the gate is located near the peak of the Seventh Hill, at an elevation of approximately 68 meters. The Byzantines built a church dedicated to Saint Romanus in the 9th century, which was later rebuilt in the 19th century under the name St. Nicholas (Hagios Nikolaos).

Fetihkapı (The Gate of St. Romanus), with an inscription about the Hadith of Prophet Muhammad on the conquest of Constantinople, on the right.

On the right side of the entrance, it is written that on the morning of 29 May 1453, the army of Fatih Sultan Mehmed (Mehmed II, the Conqueror) entered the city through this very gate after a breach opened by the cannons.

Today, locals refer to it as Cannon Gate (Topkapı) because Sultan Mehmed II conquered the city by entering through this gate, utilizing state-of-the-art cannons. On the right side of the wall, there is a Turkish inscription quoting the Prophet Muhammad’s hadith:

“Verily, Constantinople shall be conquered. Blessed is the commander who conquers it, and blessed is the army that will achieve it.”

The painting of the conquest of Constantinople shows Mehmed the Conqueror entering through the St. Romanus Gate, Fausto Zonaro.